For the last two months of their life in the United States, José Alberto González and his family spent nearly all their time in their one-bedroom Denver apartment. They didn’t speak to anyone except their roommates, another family from Venezuela.

They consulted WhatsApp messages for warnings of immigration agents in the area before leaving for the rare landscaping job or to buy groceries.

But most days at 7:20 a.m., González’s wife took their children to school.

The appeal of their children learning English in American schools, and the desire to make money, had compelled González and his wife to bring their 6- and 3-year-old on the monthslong journey to the United States.

They arrived two years ago, planning to stay for a decade. But on Feb. 28, González and his family boarded a bus from Denver to El Paso, where they would walk across the border and start the trip back to Venezuela.

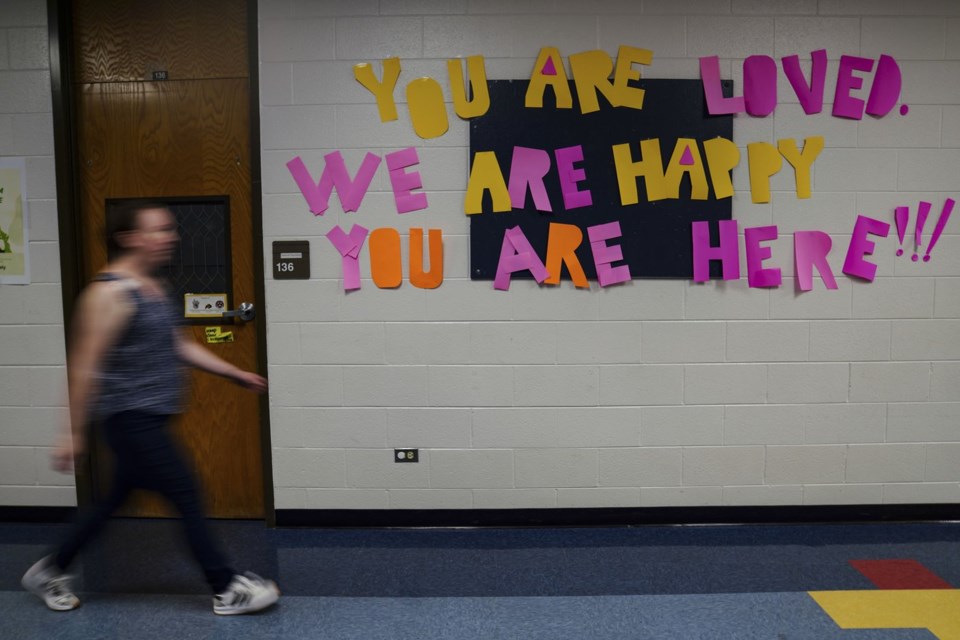

Even as immigrants in the U.S. avoid going out in public, terrified of encountering immigration authorities, families across the country are mostly sending their children to school.

That’s not to say they feel safe. In some cases, families are telling their children’s schools that they’re leaving.

Already, thousands of immigrants have notified federal authorities they plan to “self-deport,” according to the Department of Homeland Security. President Donald Trump has encouraged more families to leave by stoking fears of imprisonment, ramping up government surveillance, and offering people $1,000 and transportation out of the country.

And on Monday, the Supreme Court allowed the Trump administration to strip legal protections from hundreds of thousands of Venezuelan immigrants, potentially exposing them to deportation. Without Temporary Protective Status, even more families will weigh whether to leave the U.S., advocates say.

“The amount of fear and uncertainty that is going through parents’ heads, who could blame somebody for making a choice to leave?” said Andrea Rentería, principal of a Denver elementary school serving immigrant students.

Rumors of immigration raids on schools became a turning point

When Trump was elected in November after promising to deport immigrants and depicting Venezuelans, in particular, as gang members, González knew it was time to go. He was willing to accept the trade-off of earning just $50 weekly in his home country, where public schools operate a few hours a day.

“I don’t want to be treated like a delinquent,” González said in Spanish. “I’m from Venezuela and have tattoos. For him, that means I’m a criminal.”

It took González months to save up the more than $3,000 he needed to get his family to Venezuela on a series of buses and on foot.

They sent their children to their Denver school regularly until late February, when González’s phone lit up with messages claiming immigration agents were planning raids inside schools. That week, they kept their son home.

“Honestly, we were really scared for our boy,” González said.

In the months following Trump’s inauguration, Denver Public School attendance suffered, according to district data.

Attendance districtwide fell by 3% in February compared with the same period last year, with even steeper declines of up to 4.7% at schools primarily serving immigrant newcomer students.

Data obtained from 15 districts across eight additional states, including Texas, Alabama, Idaho and Massachusetts, showed a similar decline in school attendance after the inauguration for a few weeks. In most places, attendance rebounded sooner than in Denver.

Nationwide, schools are still reporting drops in daily attendance during weeks when there is immigration enforcement — or even rumors of Immigration and Customs Enforcement raids — in their communities, said Hedy Chang of the nonprofit Attendance Works, which helps schools address absenteeism.

In late February, González and his wife withdrew their children from school and told administrators they were returning to Venezuela. He posted a goodbye message on a Facebook group for Denver volunteers he used to find work and other help. “Thank you for everything, friends,” he posted.

Immigrant families are gathering documents they need to return home

Countries with large populations living in the United States are seeing signs of more people wanting to return home.

Applications for Brazilian passports from consulates in the U.S. increased 36% in March, compared to the previous year, according to data from the Brazilian Foreign Ministry. Guatemala reports a 5% increase over last year for passports from its nationals living in the United States.

Last month, Melvin Josué, his wife and another couple drove four hours from New Jersey to Boston to get Honduran passports for their American-born children.

It’s a step that’s taken on urgency in case these families decide life in the United States is untenable. Melvin Josué worries about what might happen if he or his wife is detained, but lately he’s more concerned with the difficulty of finding work.

Demand for his drywall crew immediately stopped amid the economic uncertainty caused by tariffs. There’s also more reluctance, he said, to hire workers here illegally.

(The Associated Press agreed to use only his first and middle name because he’s in the country illegally and fears being separated from his family.)

“I don’t know what we’ll do, but we may have to go back to Honduras,” he said. “We want to be ready.”

Trump’s offer to pay immigrants to leave and help them with transportation could hasten the departures.

González, now back in Venezuela, says he wouldn’t have accepted the money, because it would have meant registering with the U.S. government, which he no longer trusts. And that’s what he’s telling the dozens of migrants in the U.S. who contact him each week asking the best way home.

Go on your own, he tells them. Once you have the cash, it’s much easier going south than it was getting to the U.S. in the first place.

____

Associated Press writer Jocelyn Gecker contributed to this report.

___

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Bianca Vázquez Toness Of , Neal Morton And Ariel Gilreath Of The Hechinger Report And Sarah Whites-koditschek And Rebecca Griesbach Of Al.com, The Associated Press